Few genres embody the cultural and musical identity of West Africa as profoundly as highlife. Highlife enshrines the essence of West African history—a genre whose very foundation is built on influences from various ethnic groups, genders, races, and religions, cutting through borders. Often overshadowed by the Global landmarks of contemporary genres such as Afrobeats and Street pop, it often falls short of representation on the world stage.

As a region that has struggled with historical documentation, analysing the origin of highlife gives a chronological background of our society, spanning centuries and notable events—from periods of slavery to the colonial days after its abolishment down to post-colonial Africa.

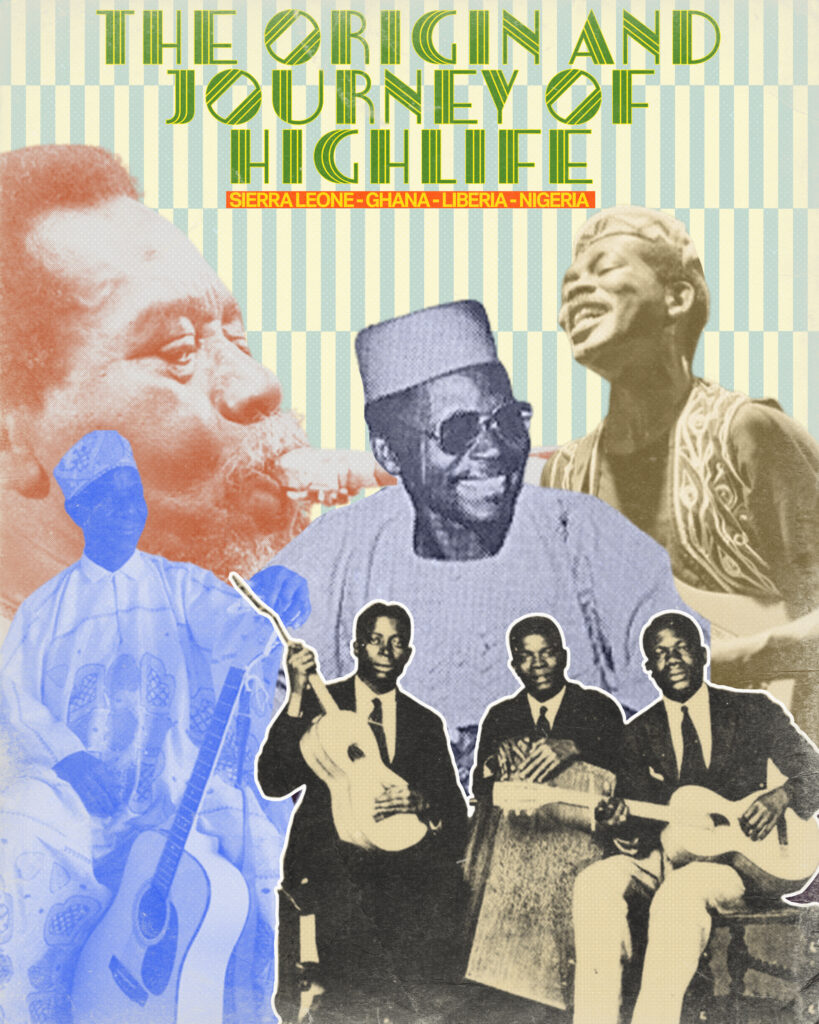

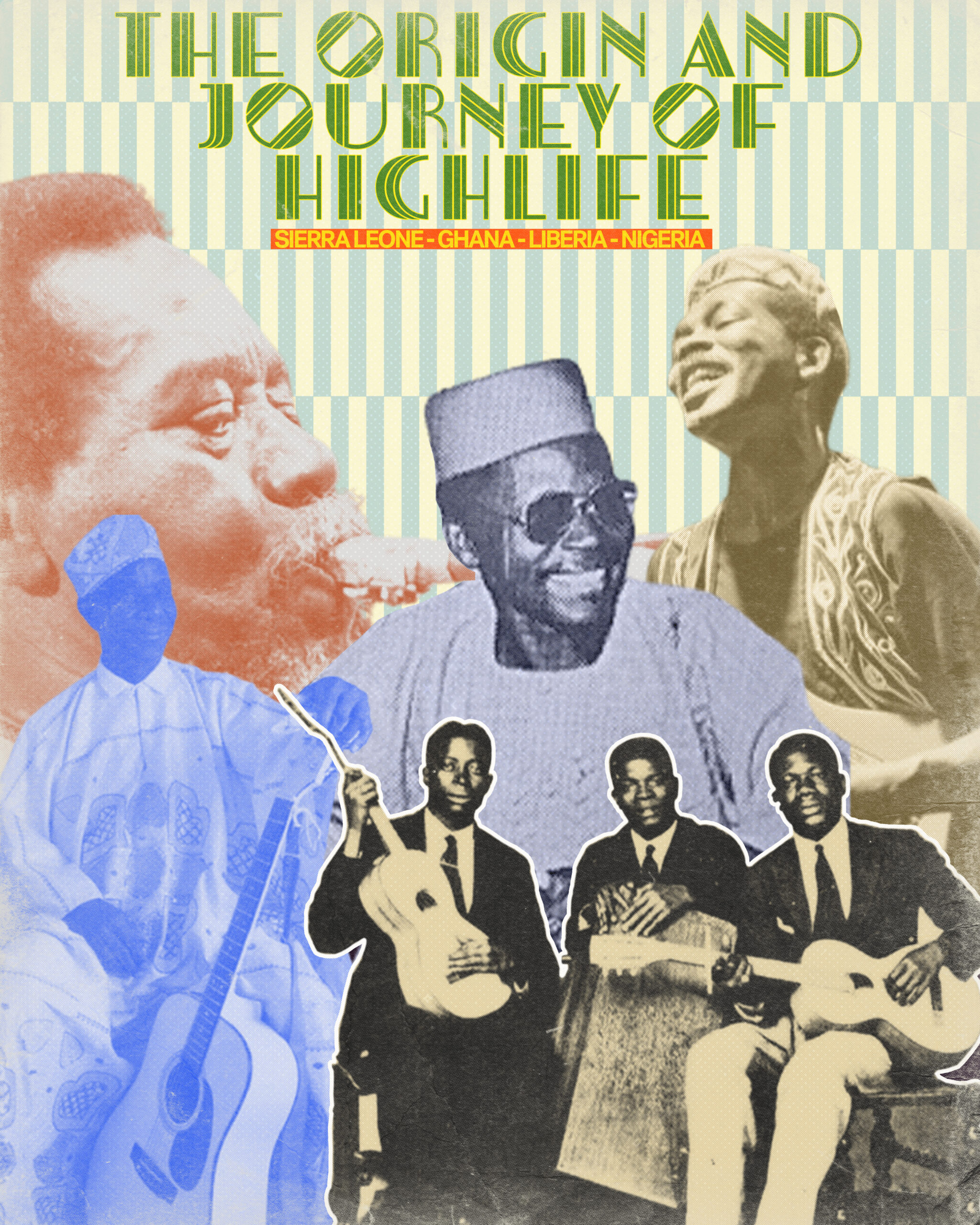

Due to its many iterations (credited to the constant travels of Africans, whether through slavery, seeking asylum or exploration), the place of birth of highlife is frequently argued, with major stakeholders in this debate being Ghana, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Nigeria.

To trace its origins, we examine the three main varieties of Highlife and their emergence in the African music scene. Dissecting this would give us a comprehensive knowledge of the roots of highlife.

Highlife is subdivided into the guitar style, brass band style and the ballroom dance orchestra. Each possesses a distinct style, conceived from the cross-fertilization between the White culture and the African culture.

We begin our review with the Ballroom Dance Orchestra, which is easily the most recognisable version of Highlife. Known for its distinct blend of African instruments in a similar format to the European orchestra—with the major replacement being the African drums (such as the Gumbe) in percussion—the other instruments kept in the mix are traditional Western instruments, being played with African techniques.

The Ballroom Dance Orchestra plays a primary role in coining the term “Highlife”. The word highlife emerged within the framework of the Ballroom Dance Orchestra in the 1920s, when the street people had to describe their songs being conducted by high-class Ghanaian bands, giving it the name “high-class life music”– Highlife music.

The Highlife Ballroom Dance Orchestra consists of the reorganisation of Western orchestral instruments with African rhythmic elements, creating a unique musical fusion. It typically features a brass section (trumpets, trombones, saxophones) influenced by jazz and military bands, a rhythm or percussion section (drums, claves, maracas) incorporating African polyrhythms, and a strings and guitar section providing syncopated grooves. Keyboards, pianos, accordions and sometimes harmonicas are also utilised to add more sonic depth.

Although “Highlife” was coined in the 1920s, it had existed in other forms, taking on various names before the 20th century. One of these established connotations is the Guitar Style. The Guitar Style of highlife percolated from Kru sailors (indigenous to eastern Liberia and western Ivory Coast) hired by European and American ship captains and merchants to work on their ships in the 1890s. The Kru people would sow seeds of highlife at various points during their travels, from Sierra Leone to Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, all the way to Angola.

The Kru sailors had learnt how to play the Spanish guitar from the ship captains. The turning point would be the Africanization of the guitar. They had re-engineered the style of play– rather than utilizing the conventional four-finger picking technique, they opted for the traditional two-finger finger picking technique used in playing the African Lute.

Over time, the Kru style simmered down the Ghanaian society; it developed into various forms, notably Mainline, Nyamposa, and Dagomba. These three styles are the basis of the standard Ghanian Guiter style highlife. While all this was taking place on the coast where the sailors and fishermen gathered, ultimately it moved into the hinterland where it came in contact with a traditional stringed instrument called the Seperewa. The guitar would gradually supersede the Seperewa as a stringed instrument, but it took over a lot of the Seperewa music and even took on the name of the Seperewa music known as Adonson (or Adowa Nsuan).

The Adonson music was a more generic sound; it concentrated more on African harmonics, focusing on the modal, moving between two tone centres, a full tone apart. Eventually, the locals would rhyme this, either in 4×4 time or 6×8 (Adowa) time. Collectively, all this became Palm Wine Music, but it wouldn’t be named Palm Wine Music until the 1940s. The introduction of the electric guitar led to the distinction of music previously played on the traditional box guitar, which became known as Palm Wine Music.

The final and earliest form of highlife is the Brass Band Style. The Ghanaian members of the British colonial army had already been trained to play the “Oompa-Oompa” brass instruments in the 1830s. These instruments were brass instruments, particularly featuring the trumpet, trombone, tuba, and euphonium. Although this was an antecedent of what Highlife would become, this is not how it was born.

Throughout the Anglo-Ashanti War, the British army recruited about 6,000 West Indians (in batches of 200) from the English-speaking Caribbean (between 1873 and 1900). The British believed the West Indian soldiers were better suited to the African climate and diseases compared to European troops. Through cross-continental travel, the West Indians brought their music along, ushering in the reinvention of African music.

The Ghanaians who had been playing the official brass band music in Western style suddenly began to see black marching bands performing syncopated music and dancing in the streets of Cape Coast. They were inspired by this and began imitating these performances. Some of the Caribbean tunes would later be incorporated into this new style.

Other styles and techniques would also be introduced, cumulating into what the Brass Band Style is recognized for, one of those styles being Jazz music.

As we conclude our exploration of Highlife, we see that its evolution is more than a musical journey—it’s a living narrative of cultural interactions, from its humble origins from the coastal areas to the streets of West Africa, to its transformative influence on global sounds.

Outside the institutional playing style, we would like to believe that highlife still lives in grandeur today, whether through the traditional playing styles by contemporary bands or through its distinct sound recognizable in modern genres; it lives on.

The Origin And Journey Of Highlife